RETRO MODERN

SAM CRANSTOUN

RETRO MODERN

4 – 18 July, 2015

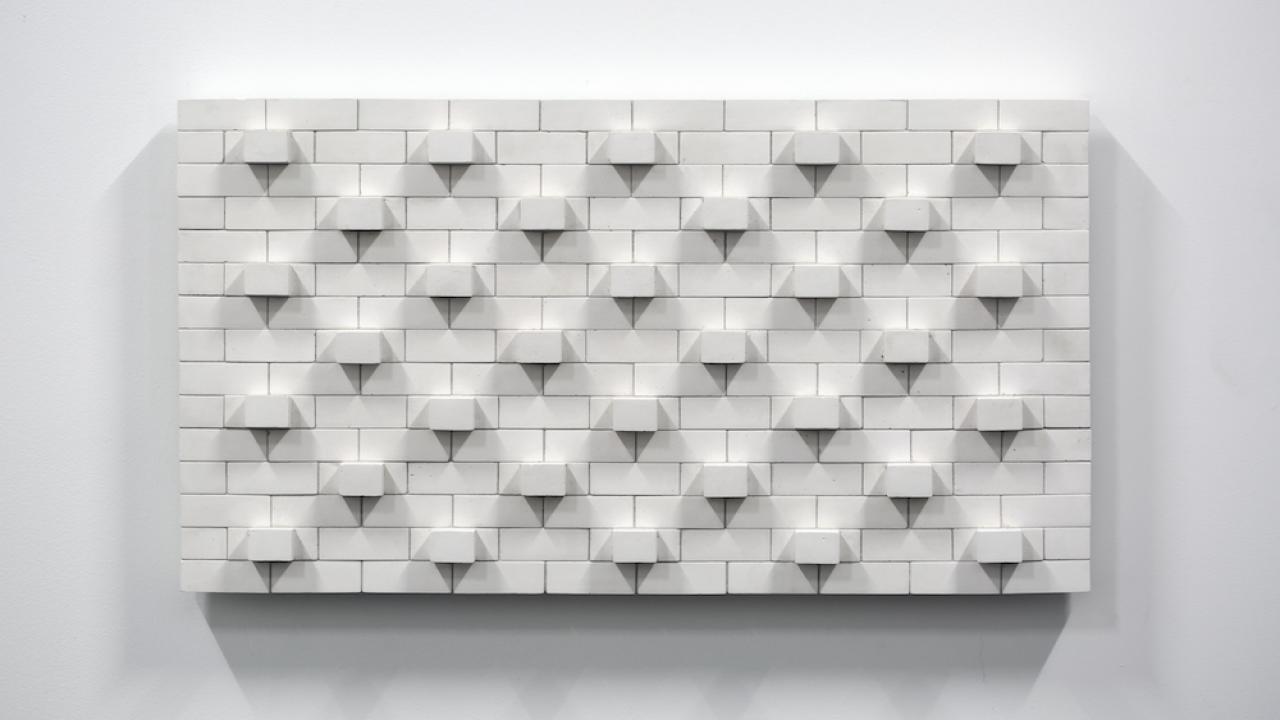

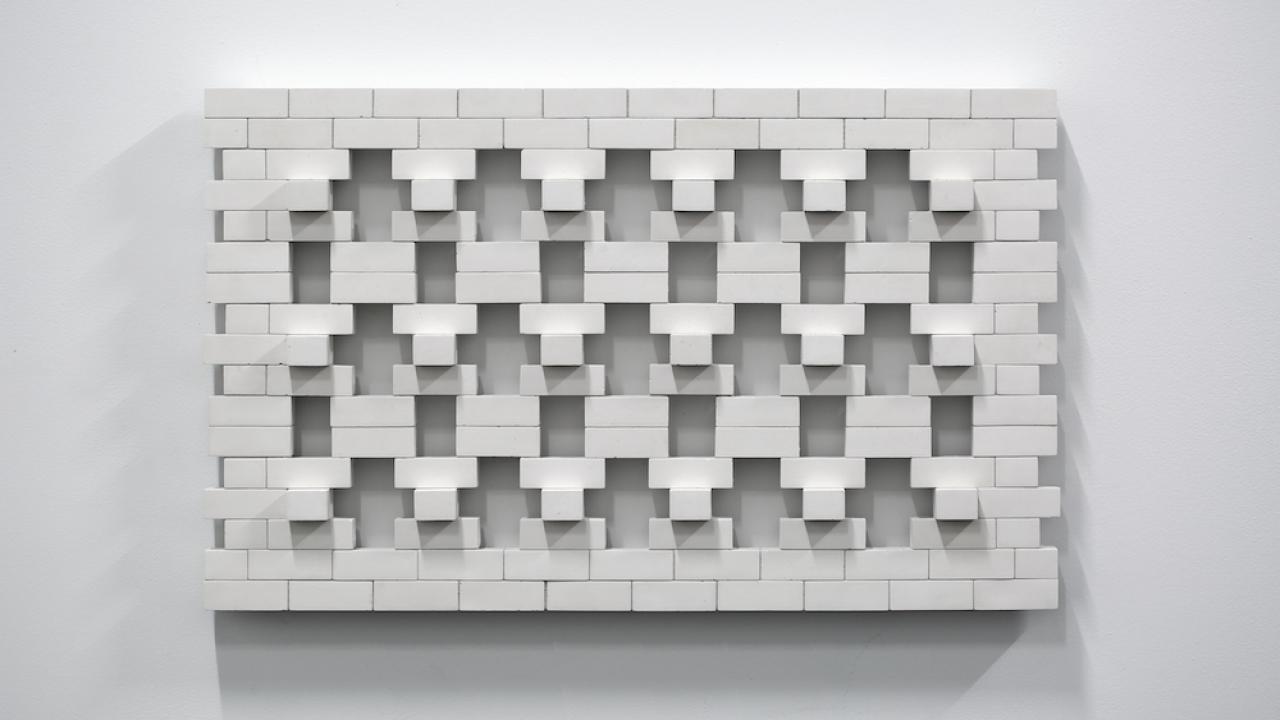

Nowhere is the rapid twentieth-century expansion of suburban Australia more evident than on the Gold Coast. From simple single-storey dwellings with accompanying carport and breezeblock retaining wall, to the ubiquitous blonde-brick six-pack apartment blocks, the coast’s rich identity is shaped by its architecture. This regionally specific brand of architecture, an instantly recognisable style that both subtly and awkwardly draws from the visual language of mid-century modernism, is at the heart of Sam Cranstoun’s latest exhibition, Retro Modern, at The Walls. As its starting point, this new series of sculptures borrows from the patterns of the building facades and retaining walls seen throughout the Gold Coast. But by simplifying these patterns, reducing them to scaled-down monochromatic forms, the former glory of these designs is restored. Once associated with a local and potentially dated style of architecture, this visual style is re-examined, reconsidered. The focus is returned to the origins of this architectural style and its place within a rich history of art and design, as well as acknowledging the utopian aspirations of its modernist heritage.

Cranstoun’s practice investigates how systems of representation shape a collective understanding of the past. Through the use of painting, drawing, photography, film, sculpture and installation, Cranstoun’s work looks at how history is shaped by different flawed, predominantly visual, systems of representation. These investigations often revolve around different historical periods, events and figures, and incorporate research from a wide range of sources. His practice aims to explore the contemporary relevance of the monument, how the monument functions as a tool to assist memory and the roles assumed by the artist when exploring historical work, namely the artist as amateur researcher, as tourist, as fan, and as pilgrim.

_

How modernism reached Australia, went awry; or vice versa

Modernism, and especially in modernist architecture, was inherently concerned with the attainment of a pure set of forms − a utopian schema. By embracing machine production, good design would be accessible to the people, especially the working class. The roots of Modernism began with an embracing of an aesthetic informed by the factory and industry. The Deutsche Werkbund, a 1907 German collective of architects, designers and artists including Austrians Peter Behrens and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as well as German Walter Gropius saw the factory as a promising symbol – a site of employment and a system that championed affordability through mass manufacturing. Their first structure, the AEG factory in Berlin is a testament to this belief. This interest in the worker informed the quasi-socialist format of the Bauhaus school, set up by Gropius in Weimar, Germany in 1919, and concerned with applying contemporary and industrial materials like glass and steel to architectural contexts that provided benefit to those who were housed or employed within their structures. Gropius’ famous adage, “form follows function” was born here.

Unfortunately, the Bauhaus and the aesthetic of accessibility that they promoted suffered from their own inherent contradiction and rhetoric. Entry to the Bauhaus was costly. Women were funneled away from architecture and industrial design, and into textiles and ceramics.1 Colour theory tutor Johannes Itten led a cult-like sub-group informed loosely by the tenets of Buddhism and vegetarianism.2 By the end of the 1920s Gropius gave up his directorship, initially to Marcel Breuer (designer of the iconic Wassily chair) and finally to Mies van der Rohe. In opposition to Gropius, Mies had aspirations for Bauhaus to be the pre-eminent global architecture and design school. He shifted the focus from utilitarian materials towards expensive luxuries like marble, onyx and rare tropical timbers. Though first seen in Mies’ Tugendhat House, his interest in achieving global attention and building with high quality materials coalesced in his 1929 German Pavilion for the International Exposition in Barcelona. Documented in Jeff Wall’s Morning Cleaning, Mies van der Rohe Foundation, Barcelona 1999, we see a familiar interior; a stark, unattainable luxury bastardised ad nauseam to this day on the pages of glossy magazines like House & Garden. In the background, next to a Mies-designed studded leather Barcelona chair, a no doubt lowly paid worker mops the marble floor.3

The abstraction of the modernist code through time is an interest that reappears throughout Brisbane-based artist Sam Cranstoun’s work. In his 2012 exhibition, ‘Fox River Rising’, Cranstoun recreates in exacting graphite detail Mies’ famous Farnsworth House. Cranstoun coyly depicts the home on accentuated, almost stilt-like foundations. Portrayed as a victim of rising sea levels, in a separate work from the same exhibition, Cranstoun lifts a Barcelona chair onto four milk crates. Desperate times call for desperate measures, with the iconic chair imagined as effectively ‘rubbing shoulders with the masses’, reliant upon the brawn of the ‘factory worker’ as crate to lift it above the floodwaters. For ‘Retro Modern’, Cranstoun has turned his attention to the modernist legacy of mid-century Queensland architecture – casting similar, subtle aspersions to the social aspirations of the post-war building projects in Brisbane and the Gold Coast.

Modernism in Australia had only reached half-mast by mid century. At this point, it was importantly still belaboured by the misconception that it meant quantifiably improved living conditions across the board. We suffered from a decade’s lag due to our distance, but did eventually feel the Bauhaus set’s influence through a trickle-down, brain drain driven by the events of the Second World War. As Europe collapsed, figures of the ‘International Style’ fled abroad; Mies to America, Gropius and Breuer initially to the United Kingdom. From their new vantage points in architectural practices or academic positions in the USA and UK, their vision for the Modern aesthetic was instilled in the next generation. This new guard reached Australia and New Zealand in the forms of Harry Seidler, arguably the most prominent in the former, and Ernst Plischke in the latter. In Queensland, one of our more prominent modernists was Dr Karl Langer, who moved to Brisbane in the 1930s to take up Professorship at the University of Queensland. 4 Despite increased confidence in regional styles, the country still looked desperately to Europe for approval. 5 The first ever exhibition of Australian architecture in London elicited a vicious response from The Observer when reviewing the show, succinctly stating “there is no Australian architecture.” 6

Taking direct inspiration from ‘six-pack’ flats, apartments and housing in Brisbane and the Gold Coast, Cranstoun has sampled breezeblock retaining wall designs, used in brick developments in the 1950s and 60s to allow cross breezes without sacrificing the privacy of occupants. These buildings and spaces have gained viral traction in recent years as the fetishised nests of design nuts. Made with plaster and a standard brick mould, Cranstoun has rebuilt six compositions for ‘Retro Modern’, installing them in close proximity to their original residential contexts. This setting allows some nice opportunities. There is a fluctuation in the weave of the bricks, from work to work, that would not be apparent in their normal occupation. An opening and closing of visibility, like lids on an eye. They are, of course, also relevant to a heritage of geometric abstraction. As an unashamed aesthete, Cranstoun does not deny the simple, visual pleasure of their form and repeated application. But this does not need also deny meaning. Flat against the wall, these patterns are without point – they no longer let air nor vision travel through. In this way, I see ‘Retro Modern’ as an acknowledgement of a design principle that succeeded in capturing the attention of the world, but one that has ultimately withered on the vine, waylaid by capital and aspiration. They are without function, and thus by deduction, now art.

Tim Walsh, July 2015

NOTES

1 Jonathan Glancey ‘Haus proud: The women of Bauhaus’, The Guardian, Accessed online 2 July 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/nov/07/the-women-of-bauhaus

2 Magdalena Droste, Bauhaus: 1919-1933, Taschen, 2002, pp 24-32

3 For further examples of the ongoing labour involved in maintaining modernist houses, see Ila Bêka & Louise Lemoine’s film Koolhaas House Life, which documents housekeeper Guadalupe Acedo’s ongoing cleaning of Rem Koolhaas’s 1998 building Maison à Bordeaux. Accessed online 2 July 2015: https://vimeo.com/21876246

4 Beyond their interest in progressing architecture, Seidler, Plischke and Langer held other similarities – they were all Austrian émigré, Plischke and Langer both studied under famed Austrian architect Peter Behrens

5 Evidenced amusingly by the 1956 April-June issue of Architecture in Australia and the article entitled ‘England sees us for the first time…with interest!’, Accessed online 24 June 2015, http://qldarch.net/beta/#/article?articleId=aHR0cDovL3FsZGFyY2gubmV0L29tZWthL2l0ZW1zL3Nob3cvMTIyNw

6 Ibid, p. 62